They have not changed for millions of years and still fascinate people all over the world: tortoises. A particularly beautiful species lives in the south of Madagascar: the Radiated Tortoise (Astrochelys radiata). Its history begins long, long before the first people came to Madagascar. But it was not until 1802 that the Englishman George Shaw described the Radiated Tortoise. He himself had never visited Madagascar, however, but was curator of the British Museum in London, whose collection of animal preparations he supervised. A century earlier, the English microscopist Nehemiah Grew had described specimens of a large tortoise from Madagascar, but attributed them to the South African native species of the Geometric Tortoise (Psammobates geometricus) because of their similar appearance. Only Shaw described them as a species of their own due to the clear external differences – but also considered in his first description whether the animals would not also occur on Jamaica.

As one knows today, the only habitat of the Radiated Tortoise is the south of Madagascar. It lives in the remaining thorn forests and on limestone plateaus from Amboasary in the central south to Toliara (Tuléar) on the southwest coast. The daily routine of a Radiated Tortoise begins in the morning with warming up in the first rays of the sun. When an animal is at operating temperature, it begins to search for food. Since tortoises live mainly from the barren grasses and low bushes of the spiny forests, the search for food takes many hours every day. The animals can only take in water in the dry, all-season very hot environment from smaller puddles or in the form of dew in the morning hours.

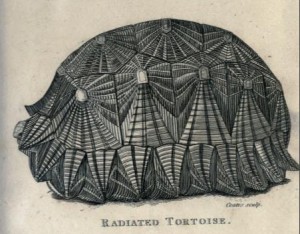

Adult tortoises can reach a shell length of almost 40 cm with an impressive weight of 10 to 15 kg. The females remain a little smaller than their counterparts. Every Radiated Tortoise has – similar to a human fingerprint – its own, unmistakable ray pattern on the round shell, on which it can be recognized for a lifetime. Despite their size and striking pattern, the animals are often hard to spot between thornbushes and sand – a miracle of nature.

During mating during the short rainy season, the male balances its heavy shell on that of the female – and even emits quiet squeaks. A single insemination can be used for several clutches at intervals of four to six weeks. Usually a female lays up to three clutches per season, each with three perfectly round, white, hard-shelled eggs. She digs a hole with her hind legs into the sandy soil, which she later carefully covers up again. However, it takes seven to eight months before small tortoises actually hatch out of the eggs. The young tortoises are just three or four centimetres long and are highly threatened by predators such as tenrecs, lemurs and birds. Once grown up, they have hardly any natural enemies and can live for up to a hundred years.

The endangerment of the Radiated Tortoise has strongly increased in the last decades. Their habitat is dwindling visibly due to slash-and-burn agriculture and zebus, the remaining spiny forests are being dismembered further and further. Within 10 years, the original habitat has decimated to just half. Hundreds of animals are illegally collected from the habitats and transported to larger cities for sale. Almost every month, smugglers make headlines when hundreds of young animals are found in suitcases again at the airport. In 2018, the record reached almost 11,000 confiscated tortoises in Toliara (Tuléar) in one day, a sad fame. All animals should have been smuggled to Asia. Ten years ago, in southern Madagascar, one had to stop every few hundred meters on many roads to carry a tortoise out of the danger zone. Today, one hardly finds a single animal along the sand tracks for several hundred kilometers. They are sold abroad for the illegal pet market and traditional Chinese medicine, although legal offspring from healthy stocks would have been available in many countries for a long time. Others are simply eaten. The Mahafaly and Antandroy, whose regions cover a large part of the tortoise habitat, have a fady that does not allow tortoises to be caught or eaten. However, this taboo does not affect the more and more immigrant or transiting ethnic groups or non-Madagascans. More and more illegal private keeping of Radiated Tortoises is increasing all over Madagascar. Animals are kept in backyards and houses as symbols of wealth and high social status. They are often found in hen houses because Radiated Tortoises, according to a myth, keep diseases away from the poultry.

Should the disappearance of the tortoises continue, the species could become extinct in 50 years. The IUCN therefore lists them on its red list as “threatened with extinction”. In the Washington Agreement on Trade in Protected Species, they are listed in Annex I, the highest level of protection. For some years now, however, there have also been protection efforts aimed at counteracting the ever shrinking population. In the coastal village Ifaty-Mangily on the southwest coast, for example, there has been a “tortoise village” since 2005, in which hundreds of confiscated tortoises are accommodated and cared for until they are released into the wild. In addition, the station takes care of the breeding of the Radiated Tortoise so that the animals can then be re-introduced to protected areas. What is still lacking, however, are patrols in national parks and other areas to protect the tortoises living there.

If you want to experience and observe the last Radiated Tortoises in their natural habitat, you should look for them in the national parks Tsimanampetsotsa and Andohahela or the reserves Reniala, Antsokay, Beza-Mahafaly or St. Marie. There they are still existing, these leisurely armoured animals with their unmistakable appearance.

Le village des tortues in Ifatyunfortunately not online up to date- Distribution, status and reproductive biology of the radiated tortoise in southwest Madagascar

Scientific article | USA 2005 | Author: Thomas Leuteritz - Observations on the diet and drinking behaviour of radiated tortoises in southwest Madagascar

Scientific article | USA 2003 | Author: Thomas Leuteritz - Reproductive ecology and egg production of the radiated tortoise in southern Madagascar

Scientific article| USA 2005 | Authors: Thomas Leuteritz, Rollande Ravolanaivo - The role of local taboos in conservation and management of species: The radiated tortoise in southern Madagascar

Scientific article | Sweden/Madagascar 2003 | Authors: Marlene Lingard et al - Population dynamics and exploitation of the radiated tortoise in Madagascar

Scientific article| Great Britain 2002 | Author: Susan O’Brien

MADAMAGAZINE Your Magazine about Madagascar

MADAMAGAZINE Your Magazine about Madagascar