That Madagascar is always good for a surprise was already clear to me on my first trip in 1995. But this trip should be a little different.

With our guests, we were on our way to the south of Madagascar, and at our stopover in Antsirabe, 170 kilometers from the capital, we settled down in a cozy hotel. Actually we wanted to leave the next morning. During dinner, my guest Josef asked me what the turning of the dead was all about. We talked for a while about this tradition, but some questions remained open for me, too. After returning to our hotel I asked the security guard Naina when, how, where, and why this funeral feast takes place. Perhaps he wasn’t so keen to explain everything in detail, at least he just said: “A Famadihana will take place in my village the day after tomorrow – if you want, you are welcome to come by”.

I was a little queasy at the thought of visiting such a private family celebration, and also a reburial of the dead, with a travel group. That same evening I spoke to friends from Madagascar. The tenor: If we would buy a zebu, it wouldn’t be a problem. At night my thoughts revolved around the upcoming festival – I wasn’t sure if it was right to visit a Famadihana with guests. I had always been against “such corpse tourism”. The next morning Naina received me in the arrival hall of the hotel and asked me how I had decided and whether we wanted to attend the celebration. I informed him of my concerns and he promptly addressed them. We wouldn’t have to buy a zebu either.

I discussed the subject with the guests over breakfast. It soon became clear that the interest in this cultural event was very high. A zebu cost about 150 € and so we put money together and asked Naina to buy a suitable animal – even if it was not a must, we wanted to contribute to the celebration with a good present.

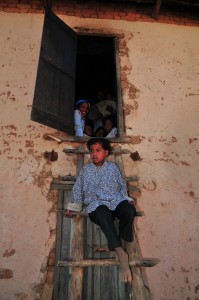

Around noon we set off to the village where the Famadihana was to take place. But when we arrived there was nothing to see of a party. The village leader greeted us and told us that a Famadihana goes on for several days. Today, the arrival of guests from the other regions of Madagascar was to be expected, and tomorrow it would really get going. We spent the afternoon in the village and were encouraged by the inhabitants to take a closer look. Thus our travel group quickly dissolved, and every guest was integrated into the village life. When our guests unpacked their cameras to document everything, of course, the village visitors (besides the inhabitants themselves) also wanted to be photographed. This expanded into a huge photo session, which lasted until we left the village in the late afternoon.

The next morning we went back to the village, and this time we were greeted with shrill sounds of antique musical instruments. A lot of people were busy walking around. Our guard Naina was already in the village, welcomed us, and told us that our zebu would be delivered immediately. The already cut up zebu was brought with a Pousse-Pousse, and the women of the village prepared it directly with rice in big pots on their fireplaces. The hump of the zebu, for Madagascans the best piece of the whole animal, was given to the direct relatives of the dead of the Famadihana.

For hours we celebrated with a lot of music, a lot of food and even more people. I and the guests were right in the middle of it, celebrated with the Madagascans, ate rice and zebu, and were allowed to photograph everything. In a small Kabary, the village leader thanked the numerous guests for coming and for the great interest in honoring the dead. The relatives, invited guests and acquaintances gradually collected money for the Famadihana, which is very cost-intensive for the relatives of the dead due to the large celebration with many guests. Some families are in debt for years in order to host a Famadihana for their deceased. There is no fixed annual rhythm in which the Famadihana must take place, only a maximum distance – I believe it is ten years – must be maintained. Any number of Famadihanas can take place in between. A Famadihana is common in the highlands every seven years.

It is usually held when relatives have raised enough money or when important events have taken place in which the deceased should definitely participate. The villagers believe that the dead ancestors guide the fate of the living in everyday life. The Famadihana thus honors the dead and ensures a kind of regular “communication” with the deceased. In the evening we took many impressions of an exuberant celebration back to the hotel.

On the third day, it was time for the “real” Famadihana. Early in the morning, we reached the village. I had brought a few baguettes because there is seldom bread for the villagers and it should be part of a party. The villagers were all dressed festively today, wearing colorful robes, festive jewelry and the musicians were back again and provided for noisy background music for the dances. Around noon the celebrating company – including us in the midst of the relatives – went to a hill on which the family tomb was located, a splendidly painted small white “house” made of stone. Family members and guests, including the musicians, walked up the hill to the entrance of the tomb, singing, and dancing, while hundreds of people gathered on the slope. The whole village, all neighbors, acquaintances, and relatives had gathered to attend and celebrate with the Famadihana. The tomb itself had a door partially underground, which had to be uncovered by the men of the village. A narrow staircase led down to the individual “floors”, where the bones of the deceased were laid to rest.

Before the turning of the dead itself took place, the village leader held another Kabary, and this time it was more detailed than yesterday. He again thanked the many guests for coming and explained that the actual Famadihana, i.e. the reburial of the dead, would now begin. He spoke of honor and respect for the dead and apologized in advance for the disturbance of the peace associated with the opening of the family tomb and the celebration itself for the ancestors. During the Kabary, bast mats were presented into which the mortal remains were later to be transferred.

After this speech, the dead bodies, wrapped in cloths and bast mats, were taken out of the tomb. Seven family members were inside – all were taken out to participate in the celebration of the living. With some bodies one could still guess that they hadn’t died too long, others only contained loose bast mats. Respectfully and gracefully one by one was brought to light from the tomb. Afterward, family and guests marched seven times around the grave, dancing, and singing. The bodies of the deceased were carried on their hands.

When we had gone around the grave several times with the dead, the deceased were laid side by side on bast mats on the ground. Shielded from others by mats held by some relatives, the bones were wrapped in fresh cloths. Close around the mats stood the relatives, friends and all the others who had come to the festival. Then the village leader stood with the ancestors and sprinkled rum on them. He said that each of them should get something and be able to participate in our celebration. This was followed by a long, extensive Kabary. The village leader told who the deceased were, what they had done, and what they had been known for in their lives. Then he told the dead about the “small talk” of recent years: where a child was born, who his parents were, whether someone had gotten married or what else important things had happened.

After this very long and extensive part of the celebration, the deceased were transferred to the new bast mats made especially for this purpose. Once more there was a procession around the tomb, and again there was dancing and singing, while the family carried the bones above their heads. At the end of the Famadihana, the dead returned to their final resting places, and the men of the village closed the tomb.

Thus the Famadihana was over. We all went back to the village together, the guests – including us – were wordy farewelled and the people went home again. We all felt very honored and touched that we were allowed to participate in this solemn event and were welcomed by the villagers as family members. Nevertheless, I am of the opinion that such a private party – despite the many visitors and the partly festival-like character – should not become a “tourist magnet”, but must remain reserved for family members and friends. It was a nice coincidence that we were allowed to participate in it once.

The following year I visited the village again with other guests to bring 400 photos of the Famadihana and the many villagers and to express our thanks again. Since the men were working in the fields, the wife of the village leader collected all our pictures and later distributed them to the others. The joy about our present was huge, and I was happy that we could at least give something back.

MADAMAGAZINE Your Magazine about Madagascar

MADAMAGAZINE Your Magazine about Madagascar